Film Review- Death on the Nile

by Arnold Wayne Jones

More than a century after the publication of her first novel, Agatha Christie remains the best selling novelist of all time. Think about that: The only authors who are more widely read are Shakespeare (a playwright!) and God (the Bible… though maybe that should be classified under fiction as well). That’s a lot of wide-ranging appeal. On the other hand, popularity doesn’t always translate into brilliant writing. Christie’s skill was plotting more than characterization. Those who populate her novels tend to be types – chatty cousins, blustery retired soldiers, Bohemian young women, moustachioed Lotharios. They serve her stories more than they live in our imaginations.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Her more than 50 full-length books featured her most famous detective, Hercule Poirot, 33 times, and even he was something of a cipher. Fussy, stout, ageing, he exuded sexual repression channeling his puritanism into nosiness. And in a series of films starting in the 1970s, usually starring Peter Ustinov, his pinched emptiness became a delightful vessel for scenery chewing and the flamboyant “I suppose you’re all wondering why I’ve called you here” reveal. It’s fun.

So fun, in fact, that one of my favorite popcorn movies has always been 1978’s Death on the Nile, with its portmanteau of former superstars (Bette Davis! Angela Lansbury! David Niven!) – a tour of Old Hollywood glamour with a satisfying conclusion and few consequences.

Alas, our society has changed. Despite how depressingly epidemic remakes have become, old-school entertainments usually must gesture toward justifying themselves by adding a post-modern veneer. And so Kenneth Branagh’s long-delayed remake of Death on the Nile, just in theaters, begins not with a juicy teaser to set up what’s to come, but a black-and-white prologue set decades earlier, in the trenches of The Great War in Europe, when a young soldier named Hercule uses his little gray cells to best the enemy and plan a wise military attack that nonetheless has a dire result. Those scenes explain Poirot’s celibacy, his outrageous whiskers and perhaps his hesitancy to solve the crime at the center of the story. It’s not just popcorn fun anymore … it’s meaningful.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Don’t get me wrong: some of the many delights on this tour of the Nile are its dazzling costumes, its breathtaking landscapes, its glittering atmosphere and parade of beautiful stars. And anyway, most of the character work is foisted on Branagh himself, who not only directs but play Poirot (as he did in his last Christie remake, 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express), so he’s up for the challenge and happy to instill a little po-mo gravitas on this frothy confection, letting the updates imbue it with more relevance. While the novel was written and set in a much less woke decade, the changes reflect a 21st century mindset. The original cast was a lily white as an albino eating a mayonnaise sandwich on Wonder Bread during a blizzard, so retrofitting, for instance, Salome Otterbourne not as a boozy romance novelist as a black world-weary jazz guitarist seems wise and organic, while interracial and same-sex romantic entanglements reflect an unspoken reality of the era.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

And the cast turns out to deliver performances beyond their remit. Sophie Okonedo, as the aforementioned Otterbourne, has none of the drunken bravada brilliantly rendered in the original by Angela Lansbury, but replaces it with a thoughtful cynicism and air of mystery and menace. Annette Bening, always one of the screen’s most watchable actresses, embraces her role as a devious matriarch. The legendary British comedy team of Dawn French and Jennifer Saunders reunite with an unexpected divergence from the source material that nonetheless makes perfect sense, and would have even in the 1930s.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Death on the Nile has always boasted one of Christie’s most serpentine yet satisfying solutions, and one concern I had going in was whether the screenwriters would pay proper homage to the source material or muck it up just to be unexpected. Without revealing any spoilers, I can attest that many of the changes in character and plot keep you guessing without while still offering a nostalgia tour of the elements that have always made Christie’s bubblegum prose enjoyable.

Don’t mistake the stylistic updates as a pretentious rejection of the novel. This is still a drawing room murder mystery with all the ridiculous melodrama you’ve come to expect, but its careful tailoring or the saggy parts presses vintage glam into familiar clothes.

Courtesy of 20th Century Studios

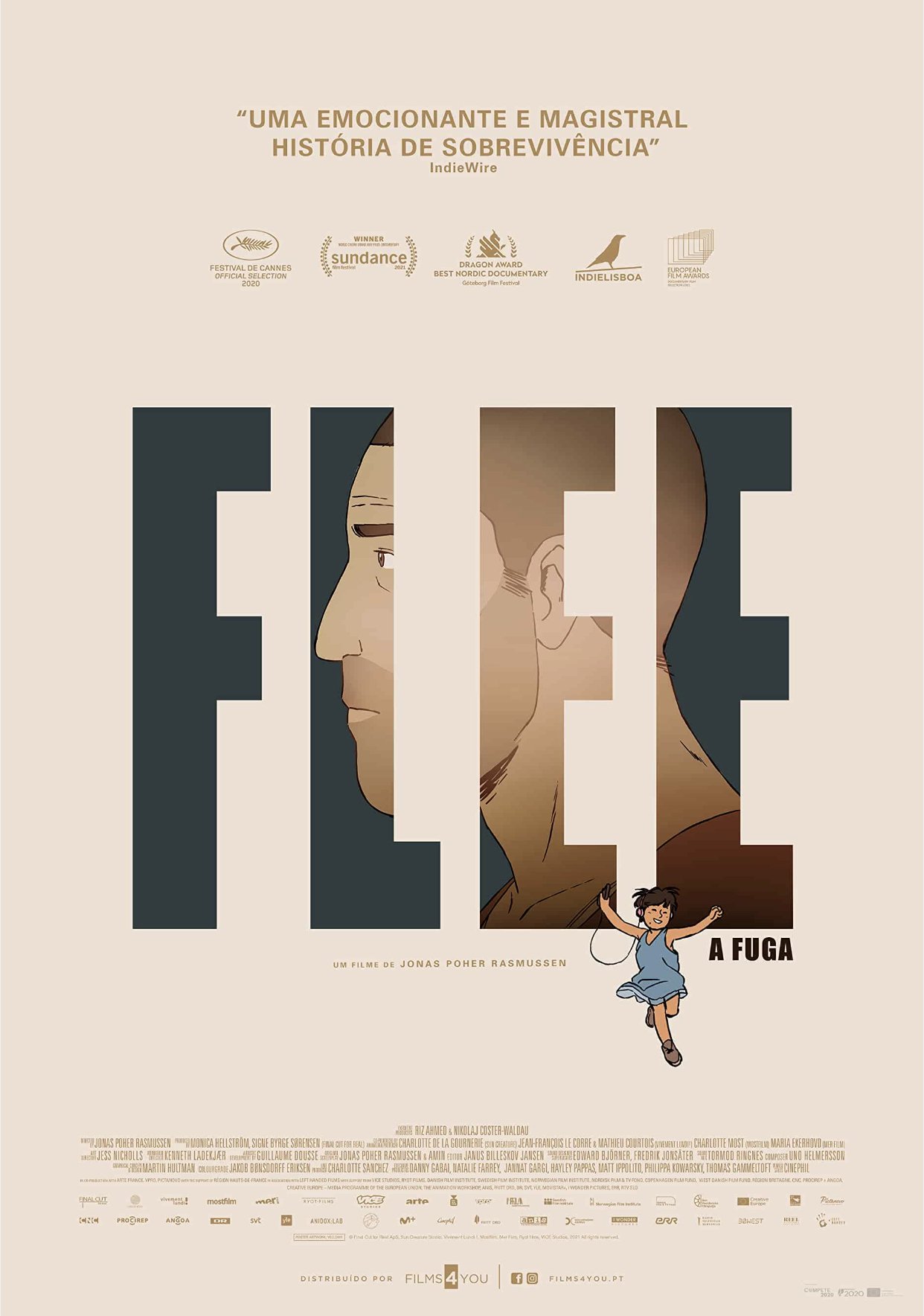

Film Review- FLEE

by Arnold Wayne Jones

By its very nature, Flee is the kind of movie that risks being reductively shuttled into the category of novelty, if not outright gimmicky: It’s a documentary, but it’s also animated (portions are intercut with life-action footage), though it uses tons of live-action footage; it touches on about a half-dozen hot-button topics, from a same-sex relationship to a same-sex relationship including a Muslim to a story about a refugee (same guy!) and he’s a refugee from the Mujahideen in Afghanistan to Russia, two countries where unrest has dominated the news for a year. Why, if it were a fiction film, they’d’ve cast Daniel Day-Lewis and let him walk away with a fourth Oscar. (They might even make him a paraplegic with a speech impediment, just to seal the deal.) The fact it is the first film ever to receive three “best film” Oscar nominations – Best International Film (it’s in Dari and Danish, as well as English and few others), Best Documentary Feature and Best Animated Feature (it’s only missing Best Picture) – could brand the guilt-watch movie of the year.

That would all be a shame, though. Try to look beyond the circumstances that almost defy you to say anything negative for fear of being canceled by the Woke Police, and see instead its bona fides: Flee is an exceptionally powerful, but emotionally accessible, film – in turns heartfelt, heartbreaking and heart-warming.

Courtesy of NEON

Flee tells the true story of Amin (voiced in the dubbed version by executive producer Riz Ahmed), looking back on his innocent childhood in Kabul before life went to shit. As a 6-year-old, Amin would think nothing of putting on his sister’s dress and playing in the streets, and though he wasn’t sexually active, he knew he was attracted to men. That made him stand out among the traditional Muslim culture, one where, as Amin recalls, “gay people didn’t exist. There wasn’t even a word for them – they brought shame upon the family.” Without the vocabulary or context to give shape to his feelings, though, he just settled in to life, a kid largely untouched by the civil war that raged along the countryside. Eventually, though, the politics and violence would hit home.

Courtesy of NEON

One of the subtle achievements of the film is how the hand-drawn animation marries with the gentle tone to conjure the authentic, quotidian experiences of an extraordinary boy living out an ordinary boyhood that was anything but ordinary. Like John Boorman’s Hope and Glory, Steven Spielberg’s rendering of J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun or more recently Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast, Flee captures the twinging melancholy of a dire situation as seen from the perspective of a callow but sensitive child unable to grasp the pending tragedy. But it layers on the component of sexual awakening to this slightly familiar trope, and shows it with delicate verisimilitude. In the present-day scenes, the affection between Amin and his fiance Kasper are sweetly loving; in the past, his comically regretful recollection of his attraction to movie muscle men like Jean-Claude Van Damme will flash familiarity to every former gay boy who knew his nature before he had the words for it.

Courtesy of NEON

Amin and his family eventually escape Afghanistan, but their precarious immigration status, harrasment by authorities, unscrupulous human traffickers and Amin’s burgeoning sexual awakening and concomitant shame make for a horrific tale of modern survival while simultaneously reinforcing the resilience of spirit, even as the situations become increasingly dire. We know it is ultimately a triumphant tale – after all, Amin lived to tell it – but it burrows deep before then, echoing the well-worn sentiment in the gay community that family is the one you make for yourself, and that it does get better.

Courtesy of NEON

The slightly staccato anime style recalls Miyazaki’s wistful memory films, while the “shots” where the filmmaker/interviewer is shown behind the scenes joking with Amin (behind the scenes of an animated film? Whaaa?!) and sometimes abstract images give the film its disarming meta-ness. A meta-docu-cartoon? If it sounds twee, the effect is anything but. Flee transcends its simplified logline to be something profoundly emotional.

Courtesy of NEON